Jun 23

‘Queer Lens: A History of Photography’ – Exhibit’s companion book is a remarkable collection

Jim Van Buskirk READ TIME: 1 MIN.

The first wide-ranging exhibition and catalogue to center the contributions of queer artists within the history of photography, “Queer Lens: A History of Photography” takes a sweeping and synthetic approach to illuminate a vital story of creativity, resistance, and resilience.

The pioneering exhibition, at the Getty Center in Los Angeles through September 28, is thoroughly documented and enriched in this magnificently-produced 330-page catalogue edited by Paul Martineau, curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Center, and Ryan Linkof, curator at the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art (slated to open next year).

Beginning with its end-paper reproductions of Tee A. Corinne’s solarized female nudes, the volume includes nearly 400 reproductions (figures and plates), as well as six pages of bibliographic references, an index, and illustration credits.

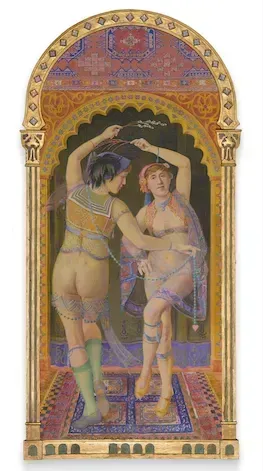

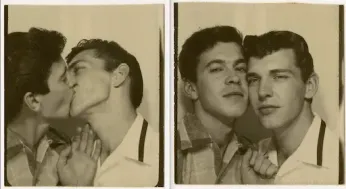

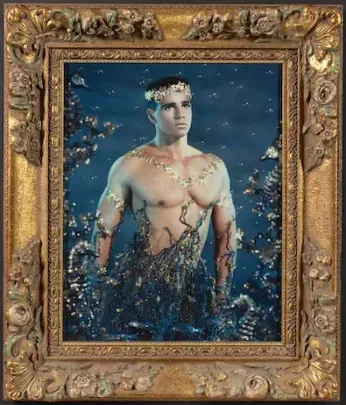

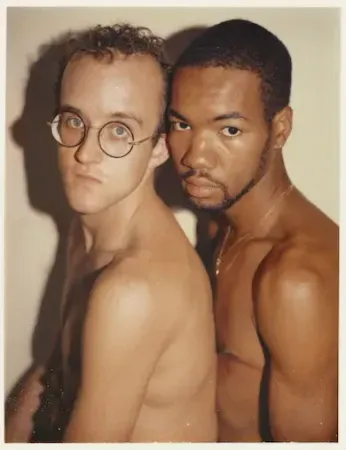

The color and black-and-white exquisitely reproduced images, presented in roughly chronological order, include formal portraits, snapshots, journalistic and artistic representations, nudes, and other depictions of queer experience by famous photographers, more obscure names, and unknown or anonymous photographers.

The curators have unearthed a wealth of seldom-seen images, including Daguerreotypes, cartes de visite, small-scale and large-format, by photographers who identify as lesbian or gay, and many who do not fit comfortably into a narrow binary. Similarly, their subjects are all over the place.

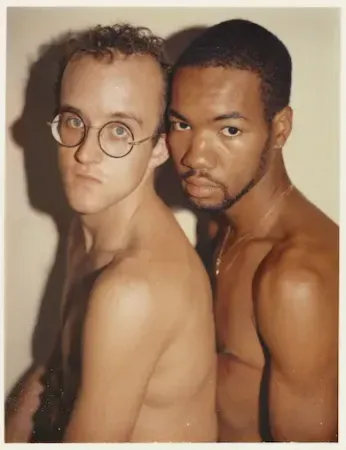

The well-known names include Edmund Teske, Andy Warhol, Diana Davies, F. Holland Day, Peter Hujar, Man Ray, Robert Mapplethorpe, David Wojnarowicz, Brassaï, Bruce of Los Angeles, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Herb Ritts, Cynthia MacAdams, among others.

The scholarly yet accessible essays add immeasurably to the volume’s value. Ken Gonzales-Day’s “Photography and the Queer Imaginary” states, “Photographic practice in the first half of the twentieth century reflected new technologies and techniques, revealed a changing understanding of human sexuality and provided for new forms of self-expression.”

Seeing and seen

In “Seeing the Overlooked: Blackness and the Queer Self-Portrait,” Derek Conrad Murray highlights the important oeuvre of Darrell Ellis, an impressively productive American Black queer artist, as well as Afro-British Rotimi Fani-Kayode, who explored intersecting themes of religion, spirituality, ethnic identity, diaspora and homoeroticism, both of whom died of AIDS.

Other hitherto neglected artists championed here are German photographer Guglielmo von Plüschow, whose studies of young Italian men inspired his cousin Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden, and Taizo Kato, renowned for his portraits of Japanese Americans.

Alexis Bard Johnson’s “Queer Visibility: Photography in American Print Culture” investigates use of photographic imagery in such post-war publications as physique magazines, ONE Magazine, Drummer, Gay Sunshine, Lesbian Tide, Sinister Wisdom, and others.

Kay Tobin Lahusen, with her life partner Barbara Gittings, championed “real life” pictures of lesbians on the cover of the Daughters of Bilitis’s monthly publication, The Ladder, and elsewhere.

In his essay, “Nothing But a Freak Convention: Queer Photography’s Hybrid origins,” Jordan Bear states that “excavating the genealogy of queer photography has long presented a special challenge for historians, for its objects can be furtive ones.” He also acknowledges “things hiding in plain sight.”

San Francisco’s presence is, as expected, woven throughout, including Minor White’s “Nude Foot, San Francisco, CA” (1947). John Gruber’s historic snapshot “Mattachine Society Christmas Party in Los Angeles, CA” (1952-53) was lent by the San Francisco Public Library’s James C. Hormel LGBTQIA Center.

Also local are Peter Berlin’s “Double Self-Portrait with Blue Jeans and Whip II” (ca. 1970), four images from Frank Melleno’s 1978 Fairoaks Baths series, Robert Giard’s portrait of Del Martin & Phylis Lyon, and Danny Nicoletta’s iconic image of Harvey Milk.

Diesel & Dorothy

David LaChapelle’s “Diesel Jeans, Victory Day, 1945,” (1994) (re)staged at Pier 45 on the S.S. Pampanito, shows Alcatraz hovering in the background. Other glimpses of San Francisco appear in work by Marc Geller, Arthur Tress, Del LaGrace Volcano, Hal Fischer, and Anthony Friedkin.

While the preponderance of the images are from the J. Paul Getty’s own extensive collection, more than forty other public and private lenders are represented, including SFMOMA.

Of course, in a work of this scope, one could easily identify gaps, e.g. important images by local photographers such as J. John Priola, Rick Gerharter, Cathy Cade, Lynda Koolish, Ann P. Meredith, Loren Cameron and Chloe Atkins. Catherine Opie’s concluding essay “To Be Seen” highlights the catalogue’s “queer experience, photography, culture,” a timeline from 1732 through 2021, before referencing her personal connection to the Bay Area: “... I thank San Francisco for coming out.”

“Friends of Dorothy,” a gallery of portraits, includes 24 various personalities from 1900 to 1923, and the text notes that in addition to the coded phrase’s usual refence to Judy Garland’s “Wizard of Oz” character Dorothy Gale, it might also “have been used by men acquainted with Dorothy Parker to gain entrance to the bar at the Garden of Allah Hotel in Hollywood.”

This unique gatefold section speaks to the power of the image and the oppositional needs for display and discretion.

Surprisingly, there is very little duplication with Jonathan Katz’s massive catalogue, “The First Homosexuals: The Birth of a New Identity, 1869-1939,” which includes a wide variety of artistic media, including photography (reviewed in last week’s issue).

Other similar books include Zorian Clayton’s “Calling the Shots: A Queer History of Photography,” (Thames and Hudson USA, 2025) highlighting the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection, and “Photography: A Queer History” (Ilex Press, 2024) by Flora Dunster and Theo Gordon.

Though nearly impossible to adequately or accurately describe, the quality of production, the depth and breadth of research, and the impressive display of many powerfully aesthetic images contribute to making this an outstanding addition to the growing body of scholarship around queer imagery.

‘Queer Lens: A History of Photography,’ Edited by Paul Martineau and Ryan Linkof, $65, Getty Publications

https://shop.getty.edu/