May 8, 2017

Sequence Six: Common Blues

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 30 MIN.

Felix was sitting on the couch when I got home. I bit down hard on a curse. After all this time I still have a reflexive displeasure, seeing him there in our house - especially when I'm just getting in from a long night at work.

And what a night it had been. My common blues were soaked through with sweat, which had made the ride home through the nippy autumn air a real treat. "I had better not be getting a cold," I said aloud as I shoved by bike through the front door. If Felix heard, he made no indication. I couldn't really see his face - he was looking at the television.

We'd plated close to four hundred entrees that evening. Everybody in the kitchen and on the floor had been running hot. The front of house staff had remained professional, poised, friendly, and attentive. They were unflappable, the best of the best, like everything else about Silverback. In the kitchen it had been a different story, though, with Kerin and Jae sniping at each other all night - trouble at home, I guess, the sort of thing couples can't help bringing with them to work.

Well, that was okay. It always gave me a kick, having a couple of lesbians serving food and wine to the same sons of bitches who were working so hard to peel their rights away from them, scrape by legal scrape, like a fish being descaled.

But then the rest of the serving staff had started getting snippy with my crew. Jobert had thrown a fit when he thought the sauce on one order of pork wasn't right - too cold, or congealed looking, or something, I didn't catch the details; the two of them burst into a sudden screaming match that startled everyone in the kitchen. Later, Jae and Romo had flared at each other over one of the dessert items, and not long after than Romo had told Steve in no uncertain terms to go fuck himself when Steve - an excellent sommelier, though he felt a need to let everybody know about his wine expertise all the time - disagreed with Romo about a pairing of mousse noisette with a pinot noir, insisting that the wine would be too thin and dry to stand up to the dessert.

I'd just about melted down a few times myself, but I've never subscribed to the notion that an executive chef and part-owner of a place like Silverback should be an autocrat, so I spent the night playing diplomat instead of dictator. After all, with Winfield Kirsch in office for the remainder of a fourth - and already, what was shaping up to be fifth -- term, we had enough strongman stuff going around already.

Still, my adrenaline was running high and I was brooding over the way the staff had turned a busy evening into Drama Night. On top of all that, I was still annoyed with my husband Klevon for the way he kept courting disaster.

From the very start of our slide toward fascism - liberties slipping away in the name of "security," so-called "prophylactic measures" being implemented to save the country from the perils of immigration and representative redistricting and full voter access, an increasingly militarized police force growing always more aggressive and hostile toward the people they were supposedly there to protect and serve - Klevon had insisted on being out, loud, and flamboyant. If I'd had my way, I'd have kept my head down and hoped to slip unnoticed through whatever horrors history was about unleash. Not my husband. I loved him for that - because I hated my own essential cowardice - but it was also a real pain to have to get up at 2:30 in the morning and go bail him out.

Which was what had happened the night before. I'd gotten home - to a nice, quiet house free of Felix, thankfully - and had a drink, then gone to bed around midnight or so. The fact that Klevon wasn't home was nothing alarming in and of itself; he often kept late hours in his studio, painting and fiddling with video projects and writing virtual reality software that would scramble realtime visual input and create transcendent psychedelic experiences. Sometimes he crashed on a ratty old sofa he kept in the studio and then just kept working all through the following day. Sometimes - not as often now days - he'd end up staying the night at some model's house. Once in a while he and Felix went to Felix's little abode, not too many blocks distant from our own much nicer home.

But when the emergency ringtone on my PCD sounded at 2:30 in the morning I knew none of those things was the case. This was going to be one of those occasions - rare, but forever etched into Klevon's permanent record, and therefore mine by extension - that he had gotten himself into some real trouble.

This time around it turned out to be the case that Klevon had been walking home at about ten o'clock when he saw two cops standing on the sidewalk, staring hard at someone. Klevon looked around and noticed a black guy standing on the other side of the street. The black guy didn't see the cops watching him; he was focused on the traffic, watching for a break that he could use to scramble across to the other side. The cops, of course, were just waiting for him to do it so they would have a pretext to pounce.

That was exactly what happened, and the cops didn't just apprehend the guy - they shoved him to the pavement, kicked him, and started beating him with their truncheons.

Klevon couldn't help himself. "Hey, ya pigs!" he screamed. "Looking to arrest a guy for being black? How's about me, then?"

"This guy was jaywalking," one of the cops drawled in response.

"You want to arrest someone for jaywalking?" Klevon darted into traffic, causing an onrushing car to lock its brakes and slide to a halt with a screech of tires. Jumping back onto the sidewalk, Klevon spread his arms. "Ta da!" he cried to the cops, who seemed unwilling to relinquish their prey so easily. So Klevon threw himself into traffic once again, and again after that, until the cops decided they had better arrest him for his own safety. They didn't shove, kick, or beat him even though he screamed profanities at them the entire time. I have a pretty good idea why tis was the case: As soon as they scanned his RIFD chip and got his retinals, they got an advisory to the effect that Klevon had friends in high places - namely, Felix.

I don't know what happened to the guy they beat up. He probably ended up in the intensive care unit, or the morgue - nobody pays much mind when cops kill someone on the streets. Nobody in power, anyway. Just do-gooders like my husband, people with drive and a fearless sense of righteousness. But I can tell you what happened to Klevon; they strip-searched him, took away his PCD, and finally, after hours had passed, allowed him to make his vaunted one phone call. He knew enough to dial my PCD's emergency number, which overrode my silence setting and triggered a ringtone nasty and loud enough to wake the dead. Seven hundred bucks was enough to get Klevon out of confinement; another three hundred fifty was enough to ensure that he wasn't charged.

So it was that upon arriving home I was tired, sweaty, aggravated, and already irritated with my husband. Seeing Felix was just about enough to break this camel's back and send me into a screaming frenzy.

Once inside the short entry hall, I shuffled and fumbled around until I got the front door shut behind me. I shouldered the bike and carried it into the small day room to the side, a room originally meant to be some sort of study or something, but now Klevon and I shared it. His bench and collection of free weights took up the far side of the room; I kept my two bikes stacked against the wall near the door. While stripping off my gloves, helmet, and reflective jacket, I took deep and deliberate breaths. The thoughts in my head were all the same old litany - why did Felix have to spend so much time here? Why didn't he just stay at his own place? But, of course, giving voice to all that would be like tugging on a thread. If I went down that road, all sorts of other shit would start churning up - jealousy, resentment, stuff I was too tired to have to sort through right now.

I stripped off more as I walked up the hall to the next door, which led into the master bedroom. Klevon had left his clothes scattered round, as always. I unbuttoned my still-damp blue tunic and tossed them onto an inviting pile of trousers, socks, and T-shirts. I could do laundry in the morning. Fishing around in my drawer, I came up with an old white wife beater that triggered fond memories of the sparkling kitchen whites from the good old days - before the working class were compelled to dress uniformly by a spate of new laws governing conduct, speech, language, and beliefs. The owner class could still dress in designer suits if they wanted - hell, they could wear loud colors, cutoffs, or paisley smoking jackets if it pleased them - but we commoners had to wear the proper blue clothing in public, unless we were at church or meeting with officials for some reason. In such cases, the civil dress code called for common grays.

Speaking of grays... I looked around for my gray King William College sweatshirt. It was where I had left it, hanging on the door to the closet - the closet Klevon had said he would clean out three weeks ago. Nothing had happened on that front, I noticed. Klevon had agreed to stay close to home today - no sense in tempting fate, or the same cops, if they were still patrolling the neighborhood -- and I'd coaxed a promised from him that he'd do a few things around the house while he was at it. So much for that. What had he been doing all day? Playing cards with Felix?

Which brought me back to the visitor sitting on the sofa. I sighed. Felix had retired from HomeSec more than a month before. In the years leading up to his retirement, I had hoped that once he was foot loose and on a pension Felix would move to Italy or something. After all, what was the point of having travel clearance, the ability to fly in and out of the country at will, if you didn't use it? But Felix seemed content to sit at home in his golden years. Our home, that is... not his.

Once more I had to stop and remind myself not to bark at Felix, not to be rude, not to make him feel unwelcome. Klevon wouldn't like it. Anyway, it wouldn't help anything. It was pretty much my own fault - I'd walked into this marriage knowing that Klevon was a polyamorist, and that was never going to change. Not for me, not for anybody. Laying into Felix would just get Klevon mad at me because, from his perspective, Felix had as much right to be in the house - which belonged to Klevon, after all - as I did.

But really, I thought. I get the whole "equal respect in equal measures, love shared with more than one life partner" thing. I don't share in it - Felix and I can be friends, most days, even if we sort of have to work at it - and I've never been sexually jealous. But did Felix really have to practically live with us?

Klevon, of course, had proposed the idea more than once that Felix just take that final step and move in with us, and Felix - ever the contrarian - simply said that he needed his space.

Yeah. By occupying our space all the time.

I took more deep, deliberate breaths.

There were other reasons why I tolerated and was even grateful for Felix. He made Klevon happy - that in itself was enough, because I love my husband, and I know I don't engage him in all the intellectual and artistic ways he needs engagement. I love to see him happy and fulfilled. If Felix can do that for him, then I'm cool with Felix, even if I will never love Felix myself, as Klevon clearly wishes I could. Shared dinners a few times a week, the occasional three-way... that was about all I could manage.

And I had other, more selfish reasons for valuing Felix. Retired or not... gay or not... he had a lot of friends, and a lot of pull, in the intelligence community. Through them he kept on top of stuff that commoners like me and Klevon were otherwise never going to know about - not that he told us much. And he provided a safe zone in an increasingly unsafe time. Felix was too wired in, too valuable to the intelligence powers that were, simply to dispense with. I possessed a degree of insulation, myself - at least, as long as I ran the most fashionable restaurant in town, the "in" spot for the jackals of congress, the honchos of police and intelligence organizations, and the powers behind various bureaucratic cabals. But fashion had a tendency to change, and who knew when I'd find my status suddenly switched from "in" to "out."

That was inevitable, of course, and when it came it could mean anything from occasional inconvenience to continual flaming hell. Right now, despite the "faith freedom" laws that allowed vendors and other business associates to deny goods and services to sexual minorities - or even to impose additional fees and enhanced rates on us, all in the name of "conscience" -- I enjoyed privileged access to the essentials of my business: Liquor licenses, inside information on the freshest and least toxic seafood, a little unofficial help when it came to labor problems or lines of credit. It was amazing how even the most ardent Believer could find his conscience salved by the prospect of having the gay restauranteur they were dealing with drop a name or pass along any business-related political gossip. But if I lost my protected status? That might mean losing those essential goods, those irreplaceable services, that all-important access.

Or it might mean things that were a lot worse: Detention, house arrest, or the horrors known only to the disappeared.

That was the new thing, and it was frightening and pervasive - exactly as it was meant to be. The disappearances were low-level, and no one talked about them in social media... not in direct ways, anyhow... but everyone knew they were happening. It was all too possible that some day Kirsch or some one of his cabinet members or his appointees could step up their campaign against "deviants" and "immoralists" and "homosexualists," as the hard religious right kept calling us. If that happened, I would be a high-profile target. So would Klevon, whose provocative art seemed to amuse the Theopublican movers and shakers. Even Felix, for all his access and expertise, might find his immunity summarily stripped away. After all, he's been recruited more than half a century ago, right out of college, in a time when the intelligence agencies were actively looking for bright young gays to join up and serve their country's security apparatuses.

What a world that must have been.

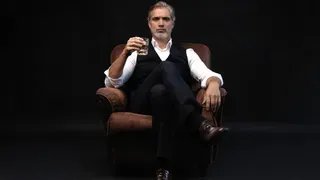

The change of clothes was comfortable, but what I really needed was a shower. Fuck it; that, too, could wait until morning. Feeling grimy, sweaty, and weary, I made my way to the kitchen - where, of course, I never cooked so much as toast. Why would I? Cooking was work; at home I wanted to unwind. To that end, I found a bottle of scotch and splashed a finger's worth into a lowball, along with a single ice cube.

Hearing the clink of ice in crystal, Felix called form the living room, "Would you bring me one, as well?"

Sure, I thought, with an angry smile on my face. Sure I'll be happy to serve you my good booze, you son of a bitch.

I did pour him a drink, but I also kept the angry smile in place as I carried it into the living room. Holding it out to Felix I was about to set aside discipline and good intentions and make some caustic remark, but then I saw the look on his face.

Something was going on. Felix traded in disappearances and attempted coups and extermination actions and all sorts of secret police stuff, and he took it all in stride. If he, of all people, was looking rattled, then something was very wrong indeed.

I sat next to him on the sofa and stared at the television. It was hard to parse what they were talking about - it sounded like another protest, another police action like so many others, a story of violence and tear gas and beatings by phalanxes of cops in body armor. In other words, everyday life under Winfield Kirsch and the paramilitary racists, xenophobes, and gay-bashers that made up his coterie of cronies.

But then one of the talking heads mentioned Milan, and another referenced Volgograd. A shock ran through me. The television images didn't seem to show any specific place; the images were blurry, jerky, badly lit. They seemed to be file video clips, many of them taken using PCDs. There was nothing definitive or distinctive about the images, just streaky lights and running people in makeshift masks. And then another of the voices on the television said the word "Baltimore." And then they said it again, and again, and I knew.

Baltimore.

"Where's Klevon?" I asked.

"He's upstairs, on the house mainframe, trying to get hold of his family," Felix said, staring at the TV, his drink untouched in his pale grasp.

"How long has this been going on?"

"First reports started up on TV about twenty minutes ago... I got a text about it..." Felix consulted his PCD with a quick glance. "Thirty-six minutes ago."

"Is it a vanishing?" I asked.

"You know we don't get those in the Untied States," Felix said. "Not with Super Cherry to shepherd us along the straight and narrow."

In Felix-speak, "Untied States" was the United States, and "Super Cherry" was President Kirsch. I felt an intense spasm of irritation at his habit of making things into a grim joke, always resorting to spook talk and referencing things in what sounded like a mockery of stupid stereotypical code names. And he could never answer a damn question; everything became a chance for his dry and irascible political commentary.

But he did have a point. We didn't officially suffer vanishings any more, not since Kirsch swept into office on a tidal wave of populist discontent. He had run the crudest campaign anyone had seen since Durrand Ruberge's famously obscene presidential candidacy and disaster of a term... half a term, actually, but it had been a reign of such terror it felt far longer. After that fiasco it seemed impossible that the chastened American people would ever elect another demagogue, but Kirsch had possessed all of Ruberge's lowest-common-denominator charm, together with a polished and statesmanlike ability to at least look like he knew what he was doing. Kirsch had made promises similar to the ones Ruberge had offered, sweeping and improbable declarations that he would "restore America" and "place hard working white Christians back in their place of pride" in the nation's social order.

Not so chastened after all, America forgot all about Ruberge and elected Kirsch president. Of course, it helped that during the Ruberge debacle voter suppression and gerrymandering had only become more systemic and entrenched, and the question of citizenship had been elevated into a Constitutional crisis that was resolved when the Supreme Court ruled that merely being born in the United States was not enough to confer citizenship onto a person, and nor was being born to parents who were citizens. A flood of litigation followed, with the eventual result being that most racial minorities and all non-Christians had lost their citizenship status, being reduced to what Kirsch had taken to calling "protectorants," as if to say that the tens of millions that had been stripped of their rights and status should feel grateful they had been allowed to remain in America at all. America, of course, could not function without these "protectorants" to do the actual work that was foundational to the economy. But why give them rights, or even wages, when their skin color, sexuality, heritage, and social class was God-given proof of their inherent inferiority?

Now, eighteen years after his election, Kirsch's wild promises had not stemmed the average white, male citizen's downward slide; he hadn't restored anyone's rights - if anything, the rescinding of minorities' rights had only served as legal precedent and justification for the government eventually coming after white trash; and the other authoritarians Kirsch had courted during his time in office, from religious leaders to military and police bigwigs, had formed a flying wedge around him to demolish what was left of America's vision of equality. The Faith Laws had only been the beginning. Now in addition to Faith Laws and Family Laws there were other suites of legislation pending: Gender Laws (to keep women subservient), Sexuality Laws (increasingly punishing to gays and lesbians), Procreation Laws (to force heterosexuals to marry by the age of twenty-eight, have children by the age of thirty, and face forced dissolution of their marriages if one partner was found to be sterile); Brother's Keeper Laws (a nice title for legislation that essentially made it legal for business owners to also own their employees and husbands to own their wives and other dependents). No one put it into words, but everyone knew these laws were designed to empower straight, white, rich males who at least pretended to believe in Christian tenets of faith.

It was just such laws, Kirsch and his cronies declared, that protected the United States from the wrath of God and immunized us from the terrifying and inexplicable phenomenon that ravaged cities around the globe - the suddenly vanishing of all human occupants. Vanishings now officially only took place in heathen countries, fallen countries like Italy and Russia and Australia, places that had earned their punishment by enacting liberal laws. The official news stories told us that when cities in the U.S. went silent, it was never because the people living in them had, as in cities in other nations, abruptly ceased to exist; rather it was always because extraordinary police actions had become necessary in those places.

No one in the media talked about the obvious fact that millions of people had dropped completely out of sight over the last fifteen years, and that major industrial disruptions had resulted when cities suddenly became empty. If the people living in those cities had all been taken to jails, as the government claimed, or even concentration labor camps, there would have been massive logistical efforts requited to transport and detain them en masse.

It's not that anyone questioned the use of concentration camps by Kirsch's government; Kirsch boasted about them, pointing to taxpayer savings that resulted from the government's partnering with private firms that constructed and maintained the facilities, firms that used the slave labor of those interned to accomplish vast infrastructure projects like the Southern Border Barrier on the cheap. But when a city's populace was "arrested" or "detained," it was the case that relatives in other cities could never located their missing loved ones, not even with offers of considerable baksheesh. No lists of prisoners were ever published; no manifests leaked to the press or accessed by hackers; and as far as anyone could tell, the concentration camps never saw an abrupt surge in acreage, facilities, or population. Contradictory stories were sometimes made public by government officials who claimed that everyone living in those cities was under some form of house arrest, and the cities had been effectively sealed off from the other side world as a form of punishment; but even here, did that make sense? How much money and manpower would it take to corral everyone in a city, ensure no one ever left, and block any and all forms of communication?

In any case, the semantic fiction that distinguished a vanishing from a police action amounted to a distinction without a difference. A so-called "police action" seemed to have the exact same end result as a vanishing. And it seemed to happen with the same sort of split-second suddenness. The last time such a police action had happened in the United States was three years earlier, when the entire population of Shreveport abruptly came in for "extreme countermeasures," ostensibly because the city fathers had declared Shreveport to be a "sanctuary city" where federal law regarding gender and sexuality would not be enforced. Shreveport was the third city in twelve years to warrant such drastic governmental response. A pattern had been established when Akron, and then Fort Worth, went dark, and that same pattern held true when Shreveport dropped off the grid: A sudden and complete loss of all connection with the city's inhabitants, followed by a sudden saturation in state media channels of reports about police actions against terrorists, or lawbreakers, or malcontents. As with the other cities, the news blackout from Shreveport had never lifted, and as year followed year there were still no answers to be had about what was going on in the city. Protesters who traveled there were summarily arrested and held without trial, or even charges, on the basis of terrorism claims.

Compare that to what Kirsch and like-minded lawmakers liked to call "the European Nightmare," even when the things they were citing as proof didn't happen in Europe. Two years after Shreveport, when all 280,000 people living in the Portuguese city of Agualva-Cacém disappeared in the space of a heartbeat, the Portuguese government declared an emergency and entered into urgent consultations with other nations that had lost city populations -- Mexico, Colombia, Uganda, Canada, South Africa, and Venezuela among them.

But not the Untied States. That sort of thing just didn't happen to God's Chosen People, Kirsch declared, and even if it did, "blaming America first" would have been the first step back toward what he dubbed "the liberal inferno of sin and decay."

Half of America believed Kirsch's every word, and trembled in fear of a God who wiped out whole cities everywhere but here. The other half of America knew Kirsch was full of shit, but they also knew he held the power of life and death over them, so they trembled too - but in fear of Kirsch's domestic spies and security agents. More than once I had heard mutters that a good vanishing was exactly what Washington, D.C. really needed.

Felix had been tapping at his PCD, checking in with contacts and reading text messages. Now he set his PCD aside and picked up his lowball, turning his focus back to the TV.

"Okay," I said to Felix. "Baltimore. So has there been a 'police action?' "

Felix sipped at his scotch, eyes never wavering from the incoherent stream of images on the screen. "Here's what my buddies tell me. At 9:15 this evening, every indication of human activity in Baltimore suddenly and completely ceased. So did electronic linkages: PCD transmissions and videoconferences cut out. Electronic monitoring failed. Automated financial transactions, routine computer feeds, everything went dark. Satellite images didn't show anything discernable, until autos started careening off course and crashing, trains plowed right past scheduled stops, and aircraft idling at the airport missed scheduled departure times."

"Any reports from incoming traffic?"

"The secret service and Homeland Security scrambled and got their field agents in place within forty-two minutes. All forms of government-overseen transport to the city - planes, trains, boats - were radioed and ordered to skirt the area and divert to other destinations. As for auto traffic, government override signals were used to halt or divert all cars that had filed Baltimore as their destination. All autos under human control were remotely commandeered. Still, a few drivers did enter the affected area before those measures were implemented. Most of them found their cars and phones were no longer sending or receiving. One couple, a man and a woman, had stopped at a diner two miles outside the affected area. When they went back to their car and found it in lockdown, they decided to ignore the shelter in place order and walked into the city. They sent out text messages and video clips that were intercepted and censored. One of my contacts is going to get me classified copies."

I looked at Felix hard, and he turned a sideways glance at me.

"There are advantages to being retained in a consulting capacity," he said, his lips flirting with the notion of a grin.

"And Klevon?"

Felix's shadow of a smile passed into a stony look. I didn't have to think of him as another husband, the way Klevon did, to see that underneath he was anxious and scared on Klevon's behalf.

"I don't know," he said. "Last I heard, Klevon wasn't having any luck getting through to anyone except his brother Frankie."

"Is Frankie still in Oregon?" I asked.

"He's on the ground in Chicago," Felix said. "At least, he was when he called Klevon. He said his connecting flight had been delayed." Felix looked back at the television now, which was showing video of a gay pride parade from fifteen years ago - the last time parades had been allowed, before the No Homo Promo laws. Then the picture cut to some talking head jabbering in a red-faced, spit-flying manner. Felix snapped his fingers at the TV and it went silent, its endless coruscation of color and light still flickering.

***

The first vanishings had taken place about fifteen years before. They had instantly thrown fuel on the fire of Kirsch's fascistic agenda and played a major part in the passage of the No Homo Promo laws and other anti-gay legislation. Klevon and I hurried to get married while we still could even though, in fact, I was reluctant to make it legal unless Klevon stopped seeing Felix.

But Felix and Klevon had been together for almost eighteen years by that point, ever since Klevon was a young man of not quite twenty, newly arrived in D.C. from Baltimore by way of James Baldwin University. They had never married; for them, it was enough just to be more or less together. Klevon had grown out of their relationship's mentor-mentee phase by then, and gotten his own house. A few best selling videalbums and a contract for his much-followed streaming personality blog had given him the money he needed to buy the place, a pre-Recurse two-story wood frame structure the likes of which had, by then, mostly been chopped up into single-room flats. Klevon had started urging Felix to move in almost as soon as the electronic signatures were affixed to the digital documents, but Felix held tight to his apartment in a three-story housing block a mile and a half away. It was important for Klevon to maintain his independence, he said, and anyway, Felix needed his space.

"He needs his space," I said to Klevon. "So why do you keep asking him to move in? And why do you keep having him over?"

Klevon just laughed at me. "You jealous?" he asked.

"No," I said, which was partly true. I didn't care that they hooked up occasionally. But I was jealous that Felix had this hold over Klevon... or anyway, the two of them had this thing between them that didn't make sense to me. It was neither here nor there, not committed and not casual either.

"We're like a married couple who understand that we work better when we're not always together," Klevon told me.

"So, again, why do you keep asking him to move in?" I demanded.

"Because he likes it here. And it's a nicer place than his dingy little flat. And I like having him around," Klevon told me.

Yeah, don't let the house-proud Felix hear you calling his place a dingy little flat, I thought. What I said aloud was: "I don't get it."

"Honey," he told me, "you don't have to. You're the newbie here, remember. What we got going on, you're never going to come between."

"So why don't you marry him?" I asked. "Why propose to me?"

"Because," Klevon said, grasping me by the jaw and looking me right in the eyes. "I want to marry you. I don't want to marry him. He's my soul mate."

That hurt me. He saw it.

"You never want to marry your soul mate," he added. "It don't work, and it hurts too much when you gotta pull away."

Which was where they were at, as it turned out, because even if they never intended to get married they had both assumed they'd stay together as a couple for the rest of their lives. But life in Kirsch's America was making it impossible, and eventually it pushed the two of them apart. That was when Klevon moved out.

"It was the memorials, the vigils, the services," Felix told me one night, about four years after I married Klevon. Felix and I were in the living room, him sitting on the sofa with a booted foot on the coffee table, me sitting in the chair at the table's end and frowning at him for having his foot on the furniture like that. But what could I say? Already, at that time, life was significantly harder than it had been for queers, and getting harder still. Felix's placement in the intel community granted him an aura of immunity that extended to Klevon and me. Anyway, it was Felix's table, which he let Klevon use since he didn't have enough space for it in his... okay, yes, fine; his dingy little flat. At least Felix thought to use coasters; our glasses of scotch gathered beads of sweat in the humid summer air, and Klevon and I would never have thought about it except that Felix made it a point to harp on. "Don't you be marking up my table with your nasty sweaty glasses," he'd say, and he was right. It would have been a shame to ruin that gorgeous dark finish.

"The wave of killings that started with lone shooter attacks," Felix said to me, his narrative little off kilter and a little disconnected. "That was a problem even before Turnip" - his name for Ruberge - "way back... I don't know... in the aughts. Or the teens." Felix was a little drunk. We had worked through a couple of glasses apiece by then. I don't remember what the occasion was. Maybe it was just a long work week, or maybe we were mutually pissed at Klevon - probably the latter, because that was right around the time Klevon was stepping out with this younger blond kid.

"We thought Turnip would bring us law and order," Felix said. "Everyone in the intel community was thrilled when he won the presidency. The feebies had practically pulled a coup to get him installed. It was always rumored HomeSec did something to a bunch of the voting machines... well, I never really believed that, but I know or a fact that a few of the CIA's pals in Moscow and Moldavia had spread fake news online and pushed a bunch of pumped-up stories on social media to discredit Turnip's opponent. We did to America what we'd done to so many other third-world countries - regime change! And it was going to do us good. The country would be grateful to us for it. And best of all, finally, we thought - we were going to get some goddamn executive support. Ha! As if. The mass shootings became coordinated bombings and well-organized terror assaults," Felix continued, in his slightly rambling, slightly drunk manner. "At first a couple a year. Then every couple of months. Then pretty much every week, and I couldn't keep doing it."

"Couldn't keep doing what?" I asked. "Intelligence work?"

Felix snorted, and reached for his glass. "With Klevon," he said.

Oh, I thought, a sort of thrill racing through me. Here it was at last: Something I had never been able to make sense of - why they two of them were together, even though they were, in many ways, apart. It wasn't just Klevon's almost political stance that he was a polyamorist and capable of loving two different people at the same time, even if those two people did not love each other.

"I will always be an intelligence guy," Felix said. "But what doesn't square with my career... with my temperament, really, is the... the whole... rallies and loudspeakers. Demonstrations. That's not how intelligence works. That sort of person, the marching protester and the firebrand on the megaphone, that's who intelligence investigates. They wanted me to file reports on him, on his associates and activities, to be sure if he was doing anything terrorist or un-American they could know about it early, maybe lay him into their own schemes and machinations."

"Who are you talking about?" I asked. I was drunk enough to have lost the thread.

"Klevon, I mean. But he wasn't dong anything like that," Felix said. "He was just angry and loud, wanted to be heard... and the grief only spurred him on. I mean, every week, every other week, it was someone, a few people. Killed at a mall. Killed on a bus that exploded. Killed by a rogue drone - or by a band of thugs... My sweet fucking saints, the meetings, the vigils, the marches... the email threads... Finally, I stepped out of the roundelay of anger and grief and... he didn't. He went to every vigil, every demonstration... every funeral."

I wondered who they lost - friends? Family? - but I didn't ask. I remembered the earlier, sporadic references Felix had made to colleagues being murdered. An office shooting? Klevon talked openly, passionately about his friends who had died. One shot to death in his own gallery for supposedly displaying "anti-Catholic" art. Another beaten by a mob of blue-shirts for being gay, beaten until his face was a ruin that would never be pretty again.

"He didn't hold it against me, said he understood. I still wanted to make it up. That's partly why I took the hate crimes analytics assignment at HomeSec. Of course, we don't track hate crimes any more, thanks to the Freedom of Faith Laws..."

I snapped out of my little flashback to the present moment, sitting on the couch with Felix, the television still offering its bleary parade of disconnected images. I look at Felix, remembering again that even if he was the interloper in our house, it was me who was the newcomer to the relationship, even all these years later.

"More scotch?" I asked.

"Naw,' Felix said, now scrolling through newsfeeds on his phone - some of them from deep in the dark web, places spooks knew about but didn't bust because they were reliable sources of useful information.

Felix's pension - lucky bastard he as, one of the very few to be getting a government pension these days - and his consultancy still paid his bills, thanks to a bit of legerdemain. Officially, under the Faith Laws, tax dollars couldn't go to faggots and dykes and other sexual mix-ups. But they could go to subcontract companies, and those companies could hire day workers for all sorts of data processing and analytic interpretive work. That's how Felix earned his income, post-retirement; that's how he kept in play with his loyal HomeSec contacts and cronies.

I was convinced for years that Felix knew something about the mass vanishings, but whenever I intimated my suspicions he coyly let me know he wasn't going to tell me anything. I was about to press him about it again, see if HomeSec had figured out any pattern to why, at random times, equally random cities would suddenly become empty of human occupants.

Just then, though, Klevon came down the stairs.

I would have expected to see him in his common grays - the nicer, more respectful clothing that people like us, people without power, would wear when meeting with an official. Certainly that was Klevon's plan, I thought. He would want to contact the government to find out more about Baltimore, find out if he could get permission to travel there, find out if anybody other than his brother Frankie had been spared from the... the "police action" that the news was describing on the television.

But he wasn't. Klevon was wearing black trousers and a bright red button-up shirt.

"Klevon," I said, starting up from the couch.

"Don't start, he said.

"Where are you going?"

"Out," Klevon said shortly, rummaging in the closet and pulling out his black leather jacket.

Clothing like that wasn't illegal - not yet - but it could get you pretty badly beaten by the cops or the paramilitary. We lived in a tolerance neighborhood - which was almost a criminal offense in itself - but even here, that shirt was way too much of a provocation.

"To a bar?" I asked.

"Protest," he said.

That was even worse. Every so-called police action had sparked protests, and the last time it had happened the mobs had been downright violent. They received violence in turn, from the cops, paramilitary groups, and private security forces.

"That's not going to help anyone," I said. "You want to commit suicide, you go to a protest. You want to do something for your family, you stop and make a plan."

"Like what?" Klevon snapped.

"Shouldn't you be talking to someone?" I asked him.

"I did," Klevon snapped. "My brother." He tuned and threw an angry glance at Felix, and this told me the real source of his rage: Klevon, too, thought Felix knew something definitive, something he wasn't sharing.

Then Klevon looked at me.

"Baltimore is fucked," he said. "And they are gonna use that to fuck us, you and me, while whatever... whatever is doing this, whatever is punishing us... while it takes the world apart bit by bit. And those motherfuckers are racing it, racing toward annihilation. Not standing up to it, not trying to find out what it is, what it wants, or how to fight it. Racing it, to see who can kill every last motherfucker on this goddamned planet."

He pulled the jacket on over the scarlet shirt, a shirt that looked like blood, that screamed for blood.

"Don't go out there like that," I told him.

Not looking back, Klevon said, "Fuck this," and slammed the door behind him.

I looked at Felix; Felix worked his PCD.

"Do you?" I asked.

"Yes," Felix said, not even pretending he needed to ask for clarification to understand my question: Do you know more than you're telling? Do you know what's going on?

I was so taken aback at his simple forthrightness I didn't know how to respond.

Felix kept tapping at his PCD. "We figured it out a while ago," he said, distracted, almost in an offhand manner.

"Jesus Henry Christ on a goddamn biscuit," I said, shocked.

Felix put is phone down and looked at me. He was calm, unblinking, just like the ops guy he'd always been. "It's a correlation of violence to population," he said. "We figured it out about three years ago. And we told Kirsch. And you want to know what that fucker said? He wanted us to find a way to let it be known, through channels that would be seen as credible but not official - I mean, via Dark Net source, underground feeds - that the government itself will perpetrate enough violence to trigger a vanishing in any city that doesn't toe the line."

"And then they'll talk about police actions and terrorists and God's wrath," I said.

"They have us building those credible non-official channels now," Felix said. "And before too much longer we'll start leaking word. Not just leaking word, but implementing action - playing this force, using it to our own advantage. Can you imagine the utility? Let's empty Cairo. Or Caracas. Or Beijing... Mumbai... Montevideo. Destabilize recalcitrant nations, force them to our will. Fine - good! But Super Cherry and his cronies won't stop there, and that's what makes it monstrous."

"They're willing to deliberately use this phenomenon on Americans?" I asked.

"Let's just say those 'sanctuary cities' are about to experience some adjustments in the real estate market." Felix's PCD pinged and he diverted his attention away from me, to whatever notice he'd received.

Why was he suddenly telling me this? Why now? Had he come clean to Klevon? Did he expect me to pass this information along? Was it out of guilt for what happened to Baltimore?

Beyond angry, beyond betrayed, I drifted out of the room. Felix was part of it. He might rationalize it any number of ways, but he was part of the whole goddamn thing. I almost admired him for his ability to compartmentalize his life the way he did - lovers, politics, work, and whatever he felt about the mysterious forces that were erasing our cities. And I did admire, even in the midst of my shock and rage, a government that could... that would... exploit the situation in such a way - a government that would outsmart God or aliens or angels or some primal force of natural justice, turning the operations of divine justice or inscrutable discipline to its own filthy, controlling uses.

In the kitchen I poured myself a fresh drink. I regarded the scotch bottle in my hand. It was a bouquet brand, the bottle made of real glass, heavy and capable, I thought, of bashing in a skull -- spilling brains -- ending a life.

I put the bottle down and took a gulp of the biting booze. If I smashed Felix's head in, the mysterious, punishing forces would see or hear or somehow know about that act of violence. I might be the one who tipped the scales and got D.C. hollowed out - everyone gone in an instant, houses and streets and offices all empty in a split second, with no radiation, no noise or chaos, just instant, diabolical peace. Clean as a whistle.

No. I couldn't and wouldn't. Violence might be part and parcel of the human modus operandi and the world we've made for ourselves, and I was sure that no matter what -- whether Klevon made it home again, whether Kirsch and his erratic fascist regime spared us or slaughtered us, no matter what -- in time, not a city would be left on the face of the Earth.

But knowing what I knew, I wouldn't try to manipulate whatever forces held us in judgment for our bloodthirsty ways. The thought of Kirsch and his cabal doing just that left me sick with dread -- how could they think they could outwit something clearly much more powerful and knowledgeable than themselves? Maybe it really was God. Or maybe it was the devil.

Whatever it was, this punitive force, this inscrutable and malicious hand that plucked at us, it could go to hell. Kirsch could go to hell. Felix, too -- though I wouldn't be the one to send him there. At the end of the day, there had to be some damned human decency left in the world.

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.