February 22, 2024

Hometown Premiere: With 'Eurydice,' Matthew Aucoin Brings Acclaimed Opera to the Boston Lyric Opera

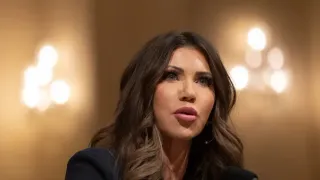

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 9 MIN.

Boston native Matthew Aucoin is a young man on the move; in the case of his revised version of the opera "Eurydice," which he composed to a libretto by playwright Sarah Ruhl, based on Ruhl's stage play, Aucoin's move is back to Beantown, where he will conduct the Boston Lyric Opera's production of his opera at the Huntington Theatre, March 1 – 10. (For performance dates, tickets, and more information, visit the Boston Lyric Opera's website.

The son of Boston Globe theater critic Don Aucoin (who, full disclosure, this correspondent served with in the Boston Theater Critics Association), Matthew played in a rock band in his youth. But opera was the musical art he chose to pursue, and at the age of 33 he has already forged a dazzling career that includes an opera about American poet Walt Whitman ("Crossing," commissioned by the Cambridge-based American Repertory Theater), a number of chamber works and orchestral compositions, a book about opera ("The Impossible Art," 2021), and, in 2018, receipt of a MacArthur Fellowship, more commonly known as the MacArthur genius grant.

With "Eurydice," Aucoin is also one of the few contemporary American composers to have his opera premiere at the Metropolitan Opera (in a co-production with the Los Angeles Opera). It was commissioned by the two companies when Aucoin was an artist in residence at the LA company. The opera premiered at the Met in November 2021 where it played for seven performances over the season.

Aucoin and Ruhl's operatic collaboration is just the latest in a long line of operatic treatments of the myth of Orpheus; in fact, the earliest surviving opera, written in 1600 by Jacopo Peri and Giulio Caccini, took on the story of the preternaturally gifted singer – a demigod whose father is the Greek deity Apollo – who ventures to the Underworld to retrieve Eurydice, the love of his life, after she is bitten by a snake and dies. Playing music that's so sad it wrings tears from the very stones, Orpheus convinces the king of the Underworld, Hades, to allow him to retrieve Eurydice and restore her to the land of the living. Hades agrees, but there's a catch: Orpheus can lead Eurydice back to the world above, but he must not look back at her until they arrive. If he does, she will be returned to the land of the dead and lost to him forever. Alas, like Lot's wife in another story about the risks of looking back at something you had before instead of focusing on the road ahead, Orpheus cannot resist glancing over his shoulder. Their tragic tale is a heartbreaker that has endured for millennia.

The big difference with previous versions is that Ruhl's text adopts Eurydice's point of view; and suggests there's more to the story, if only we're willing to hear it from a woman's perspective. (It's not necessarily kind to the male ego.) Aucoin, in setting Ruhl's text to music, conceived his own daring notion of why, at the story's crucial moment, the half-god hero looks back despite knowing what it will cost him.

In conversation with EDGE, Matthew Aucoin explained his take on Orpheus (including why he doubled the part, writing portions of Orpheus' material for two voices), reflected on the appeal of opera to the queer community, and revealed what he has in store for Boston audiences.

EDGE: I read that you regard opera as a summation of sensory experiences. I wonder if the grandeur and larger-than-life character of opera is part of why many gay men seem to find opera appealing.

Matthew Aucoin: There's such a rich history of opera and queerness. I would point anyone who hasn't read it to Wayne Koestenbaum's book "The Queen's Throat," which is a kind of personal history of gay men and opera. I think it has a lot to do with masks, as well; with this sense that, in music, you can say things that are other than the surface meaning. There's a way that I think, for centuries, opera was an art form of queer liberation, because it queers the whole nature of how human beings speak to sing in this way. Gender identities get totally scrambled... the whole history of the form is full of women impersonating men, [and of] countertenors – men singing in what is typically considered a female register.

[Opera] is another planet, and different rules apply to how human beings interact. I think it's really touching that many queer people, including a ton of gay men, found liberation in this kind of planet when the planet we actually live on was not especially conducive to queer life.

EDGE: It seems like the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice could also appeal to our community because it's about lost love, or love that is challenged.

Matthew Aucoin: A part of the story that we did not set in the opera, and that a lot of people don't know of, is that after the whole tragedy transpires, Orpheus consoles himself by having a bunch of affairs with shepherd boys. But that would be a whole other opera.

EDGE: Wow! Gotta love the classical Greeks.

[Laughter]