September 16, 2025

"Punks Not Dead" Seattle's burgeoning Queer punk scene

Lindsey Anderson READ TIME: 3 MIN.

A tragedy, there’s nothing left. What still remains in broken glass? A cloud of smoke to hide the sun. The city sings, what have you done? - “City of Rust” by FOXCULT

The last line of the lyrics to rising Seattle-based band Fox Cult’s latest single, “City of Rust,” echoes a sentiment often evoked by those who reflect on the history of the city’s punk scene. Far from its heyday in the early 1990s, when Seattle itself seemed a center of counterculture, new-millennium punks, and moody grunge rockers, today’s metropolis feels alien. Overrun with capitalist tech moguls, influencers transplanted from LA, and millennial hipsters just looking to capitalize on the latest trend (what even is a Labubu?), it can feel like the ethos that once dominated Seattle’s alternative culture has evaporated into thin air, leading many to wonder the same thing: Is punk dead in Seattle?

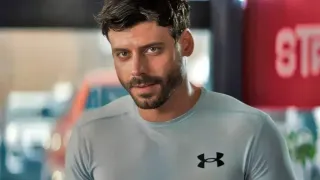

According to JR Gast, a board member of Hollow Earth Radio and co-chair at Veracity Booking, Seattle’s punk scene isn’t dead — in fact, it’s experiencing the start of a new renaissance. “I don’t think it’s dead, ‘cause I kind of just found it again,” Gast said. “I’ve been consuming a lot of not even super mainstream but more coming-up kind of music.”

Though he’s older than the typical punk, Gast said he’s finally found his community after stumbling upon small house shows. “I met all those kids, and they allowed me to be the old dude in the back, like the punk dad. I loved it,” he gushed.

According to Gast, modern Seattle punk is about more than just music. “You [make] art that talks. You can take photographs of things that matter, you can make zines. It can just be with your friends at home,” he said. “There’s a music component to it, sure, but it’s really about, like, are you doing it for yourself, and are you doing it with others?”

To be punk, one needs to meet two basic criteria, according to Gast: “[Punk] is doing it yourself and doing it for yourself. And then, it’s not about monetizing or optimizing it. It’s about having a good time and having fun and building a community.”

As co-chair at Veracity Booking, Gast helps provide up-and-coming punks with the tools they need to “do it themselves.” This means putting smaller bands in touch with spaces where they can perform and using his skills to make DIY tapes for aspiring musicians. Often, the best spaces are accessible locations, like the skate park at Cal Anderson.

Gast’s sentiment is echoed by Josh Okrent, fund developer for Seattle’s Punk Rock Flea Market. “At its core, punk is about self-determination in the face of systems that try to make people passive, compliant, or dependent,” he said. “Punk says that you don’t need permission, credentials, or institutional support to make meaning, build community, or act politically. The DIY ethic is central to that. Instead of waiting for established structures like corporations, governments, or cultural gatekeepers to provide opportunities, punk insists on creating our own.”

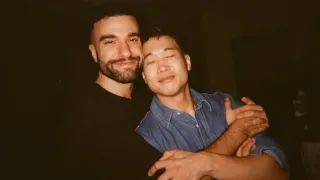

The Punk Rock Flea Market exemplifies this by providing a space for people to show up with the treasures they’ve created or found and share them with others. It’s where people can celebrate their talents and passions without relying on corporate permission. Aside from running a community bazaar, the flea market also hosts artists like Andy Iwancio, who recently performed at the latest Ghoul Party variety show hosted in the market’s Capitol Hill location.

Punk isn’t just about waxing philosophical. It’s also about walking the walk, which Okrent did in 2006 when he helped found the Punk Rock Flea Market. “There was no venue when we began,” he said. “So we made one. No one told us how to do it then, and no one is telling us how to do it now.”

Evolution

Today’s punk scene bears little resemblance to the early grunge days of Seattle. For one thing, the internet has provided people with instant connections and the potential to reach a wider audience. “It’s old-school concepts but with a new twist,” Gast said.

However, others, like Lotus Eater, a Lesbian artist and MC, think the internet has also worked to platform darker aspects of the culture. “When I started in 2023, I would have said it’s a lot closer to the grunge scene, and honestly, I think lots of aspects of it are still largely the same,” they said. “But it’s a lot more present, because a lot of people are very online.”

The punk culture is fueled by passion, which can often lead to clashes among different factions — an aspect that has been amplified in internet chatrooms and on social media. “It’s a very volatile space, and I don’t doubt that the punk and grunge scenes of the ‘90s were like that,” Lotus Eater said. “[However], everything’s more personal now. People will insult you based on a random, very obscure fact about you as opposed to fighting with you over music. People are very adamant about learning everything about somebody to be an efficient hater.”

Modern punk in Seattle isn’t devoid of superficialities. While Gast has found acceptance despite his age, many still struggle. “People can be very choosy about whether or not you’re worth being around based on things that will stop mattering when you hit 25,” Lotus Eater said.

While they’ve since found their place in punk spaces explicitly created by and for Queer people, they also recognize that superficiality can be especially toxic for younger people entering the scene — a demographic that remains large.

“[The punk scene] is more fragmented into microscenes than it once was,” reflected local punk comedian and DJ Andy Iwancio. “There’s still the tenuous relationship with providing space for all-ages shows. Thankfully, there is something great like the Vera Project and Black Lodge, but the number of venues that younger people could go to now has slimmed down, especially outside of the city.”

Having recalled the earlier days of Seattle’s punk culture, Iwancio admits, “the scene here has grown quite a lot over time.” She sees punk spaces of today evolving to unite over shared values and identities as opposed to finding camaraderie in like-minded opposition.

“I think punk as a whole has gotten a lot better and less obsessed with being ‘edgy’

Queerness and tech

Queerness is innately punk. “It is not a coincidence that punk culture and the Queer rights movement grew up in tandem,” Okrent said. “Nor is it accidental that the loud, jagged sound of punk music mirrors the jaggedness of being Queer, poor, and young in a world that wants you to remain invisible.

“Being Queer and being Punk can be seen as two sides of the same coin — a counter to mainstream culture. Punk is a mode of survival. Punk is a refusal of conformity, a way to make something beautiful out of anger, limited resources, and being markedly different in a hostile environment. Punk’s DIY ethos has given a lot of Queer people a language for both resistance and creation.”

The emergence of Queer culture as central to the new Seattle punk scene echoes the original ethos of punk as a movement to further counterculture and call out systems of oppression.

“I think the political climate is allowing that,” Gast said. “It gives some energy to it. They have something to react to again. You have this authoritarian, fascist sort of thing that’s happening; everything is getting very right-wing. It definitely spurs action where we’ve got to do it ourselves. We’ve got to do it small.”

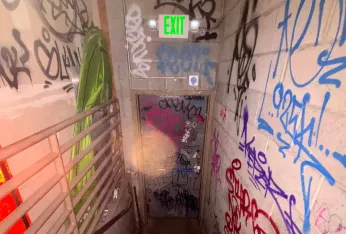

For Seattle, the growth of the tech industry has only paved the way for the punk scene’s roots to grow. “What really works for punk culture in Seattle is the boom-and-bust nature of the place,” Okrent said. “You’ll get a decade of overspeculation, with people investing money in new buildings and big structures that are totally inaccessible private spaces. But that’s inevitably followed by a stretch of failures and bankruptcies, which means that those big buildings sit there unused waiting for squatters or broke artists to do something with them.

“Punk thrives on those kinds of opportunities. And this is also essential: underneath the new layers of glass and glitz, Seattle still has a huge heart and a scrappy spirit. It’s a frontier city built on new ideas and new ways of doing things. There’s great art being made here, smart young people who resist the tech demons, and a belief that we can make a better world if the fools just get out of our way.”

Whether they’re moshing at weekend rock shows at the Cal Anderson skate park, packing in 400 sweaty fans for a house show, or showing up to the Punk Rock Flea Market to sell homemade art and found treasures, Seattle’s punks continue to show up despite the political climate working to erase them.

“Regular people, without big budgets or official backing, can create something vibrant and real, even in a place like Seattle that can feel impossibly expensive and inaccessible.” Okrent said. “And honestly, it’s not just about nostalgia or rebellion — it’s about survival. Community-built spaces teach us how to rely on each other, how to share resources, and how to stay human in a messed-up world that often treats us like consumers first and people second.”

“We want to make art, we want to express ourselves,” Gast added. When you’ve got that kind of thing stirring around you, it gives you an engine that helps you create.”

Support the Seattle Gay News: Celebrate 51 Years with Us!

As the third-oldest LGBTQIA+ newspaper in the United States, the Seattle Gay News (SGN) has been a vital independent source of news and entertainment for Seattle and the Pacific Northwest since 1974.

As we celebrate our 51st year, we need your support to continue our mission.

A monthly contribution will ensure that SGN remains a beacon of truth and a virtual gathering place for community dialogue.

Help us keep printing and providing a platform for LGBTQIA+ voices.

How you can donate!

Using this link: givebutter.com/6lZnDB

Text “SGN” to 53-555

Or Scan the QR code below!